Now that the 2022 maps have been implemented, this is our updated organizing model

The Fair Maps plan is based on SC statutes that empower 15% of voters in a county or city to petition their local government to adopt, or remove, a local law or ordinance. The law stipulates that the local government SHALL adopt the ordinance, or put it on the ballot for the citizens to vote on.

We cannot give up the fight to force our legislature to turn redistricting over to the citizens, so we must come up with creative ways to move toward this goal. Learning to use the referendum process to make our local governments more responsive and equitable is an excellent organizing tool for building the power required to force changes on a state level. (Recent state laws, primarily funded by food and hospitality corporations that rely on low-wage service work, prohibit local governments from passing wage laws above the federal minimum, or any kind of employee benefit like sick leave.)

No laws prohibit local governments from remodeling the way they practice democracy, such as implementing ranked choice voting, open primaries, or redrawing political maps. Political districts can be redrawn anytime, not just once every 10 years.

Taking over the initial building blocks of democracy will require citizens to be engaged in ways we should be now. But with our public policies directed by private profit, and political campaigns addicted to money, the basic role of “citizen” in SC has been reduced to voting in elections with predetermined outcomes every couple of years.

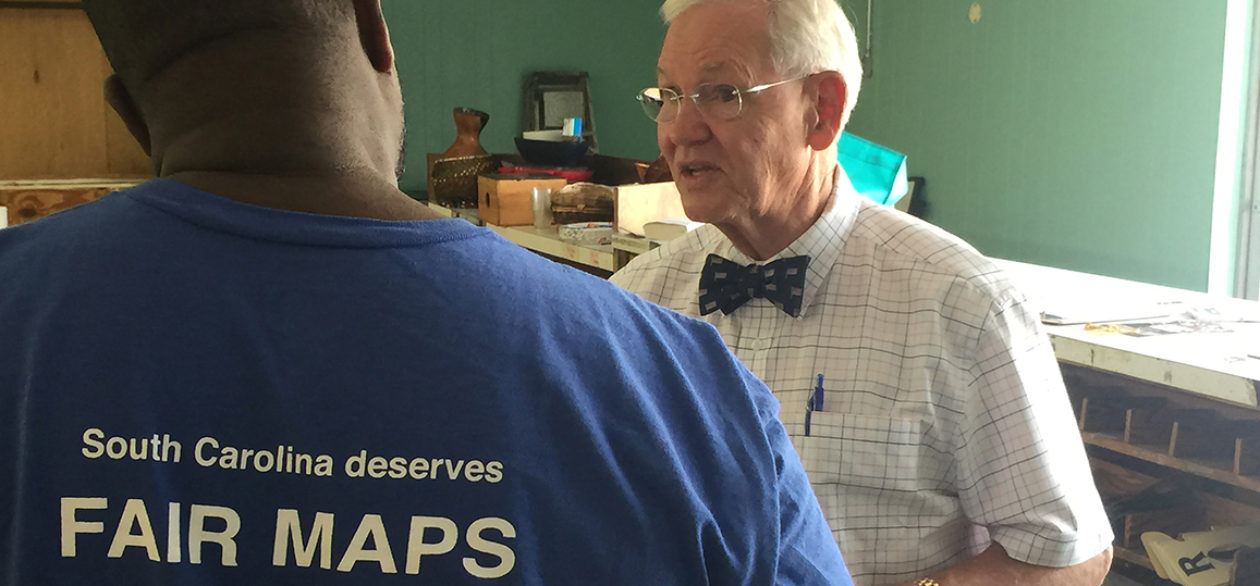

Getting rid of gerrymandering and other destructive and cruel public policies requires strategic intervention by organized and effective citizens. There must be considerable planning and shared resources before effective local campaigns can be launched. This sort of community engagement is exactly the work we must do to develop the power to make and sustain systemic change.

The Fair Maps campaign, in concert with the policy and education programs of the SC Progressive Network, will help citizens formulate local organizing plans to develop the capacity and sufficient power to make change.

To join the conversation about reconstructing democracy in SC, sign up at fairmaps@FairMapsSC.com, or call 803-661-8000.

Below is the organizing model we adopted in 2020 after the pandemic started. Because the pandemic stretched on and we didn’t raise the necessary funds, this model didn’t work. But there is a lot of good information still relevant about the need to end gerrymandering and how the Fair Maps plan is designed to do that.

One – County Pandemic Model

We are perfecting our plan during the pandemic using phones, and the Internet to keep volunteers safe. We are focusing our first phase of the Fair Maps plan on Richland County, using our contacts there to mobilize a grassroots campaign to energize the voters ahead of the November elections.

We are asking our friends in Richland County to work their contacts to help recruit petitioners, who can work from home to spread the word about our Fair Maps petitions. They will ask those who support our plan to downloaded, sign, and return the petition at our web site. Original signatures are required.

Email fairmaps@FairMapsSC.com for training opportunities. Once volunteers have been trained, they will receive a calling list sent to your phone. You do not have to live in Richland County to help with the petition campaign.

A 2016 USC survey of nearly 900 citizens revealed bipartisan support of 65% of SC voters supporting the creation of a citizens commission to draw political district maps rather than the politicians who now do so for their own benefit.

The Fair Maps SC reform effort uses state law that gives 15% of a county’s voters the power to pass a county resolution the council SHALL adopt. In this case, voters of Richland County who do not want legislators to draw their own districts will petition the council. If the council does not adopt the resolution, it must put the matter on the Nov. 3 general election ballot for that county.

So, we must get 15% of the voters of Richland County — 40,000 our of nearly 300,000 — to sign the Fair Maps petition. We must deliver them to county council by Labor Day week in order to get the resolution passed before the general election. We believe Richland County Council will pass the resolution, but if they don’t, it will go on the ballot in Richland County on Nov. 3.

Voters will win, either way.

A successful petition drive will gather more signatures than the number of votes legislators had to win their uncontested seat. Eventually, the Fair Maps campaign will have collected more votes than did the majority of the state legislature. In turn, legislators will have to respond to the legally cast votes of their constituents, and let the citizens vote on fair maps. If they don’t they risk losing in the next election. Guaranteed.

It is clear that many voters—and even many legislators—don’t understand how deeply our democracy has been gutted by partisan gerrymandering. We need to help them understand the problem, and offer a solution. We will start in Richland County. If we are successful there — and we believe that we can be — the campaign can be used as a model for replicating that success in counties across South Carolina.

On Nov. 3, most voters in South Carolina will only have one candidate on their ballot to represent them in the House or Senate. That sad reality will afford voters a deeper understanding of how gerrymandering makes a mockery of our democracy. We hope it will spur them to action.

With your help, we can do this.

• • •

Fair Maps SC Campaign Summary

The 2020 US Census that will determine how many people are in each of our state’s political districts is now under way.

The legislators who will draw the new maps for the next decade will be elected this Nov. 3. They will draw the maps prior to the 2022 election, just like they drew the maps in 2010 that created among the nation’s least democratic elections.

The candidates from the same political parties will win. And South Carolina will remain at the bottom of the quality of life charts.

Our Fair Maps SC plan was crafted by staff and legislative members of the Education Fund (501-c-3) of the SC Progressive Network, a 23-year-old nonpartisan policy institute. For this campaign to succeed, leadership must come from a bipartisan committee of established civic, business, and political leaders. The Education Fund claims no ownership or control of the campaign, but is rather a partner in a broad-based, citizen-led effort to make our elections more fair and politicians more accountable.

After a year of development, the Citizens Redistricting Commission Act was filed in December 2018 by Rep. Gilda Cobb-Hunter and Sen. Mike Fanning. We deemed our 2016 redistricting bill inadequate after a similar legislatively appointed “independent” commission in Pennsylvania grid-locked, resulting in mapping power returning to lawmakers. (See bill comparisons on page 24.)

After extensive consultation with experts across the country and studying plans that have been tried in other states, we believe that our most recent plan will work. It will require an ambitious education and mobilization campaign, but a growing number of voters understand that the current system benefits incumbents alone, and are ready to take on an unjust and dysfunctional system.

The US Supreme Court ruled recently on gerrymandering cases brought by Democrats in North Carolina and Republicans in Maryland. It found that extremely partisan maps that favor one party are not unconstitutional. Anticipating such a ruling, the Fair Maps SC campaign designed a plan that doesn’t rely on the courts or the legislature.

“The courts won’t solve the problem,” says retired state Sen. Phil Leventis. He knows better than most, as he participated in reapportionment five times between 1980 and 2012. “Elected officials protecting themselves is the problem, so it is incumbent on us as citizens to take our elections back. Democrats, Republicans, Independents — anybody and everybody who values democracy can make elections work much better than they are today.”

Our plan would create a commission of qualified citizen volunteers, picked like a jury pool, whose final maps cannot be changed by the legislature or by veto. As in 27 other states, SC voters can’t place a constitutional amendment on the general election ballot. The three states that have created independent citizens commissions have done so through statewide ballot initiatives. They are California, Colorado, and Michigan.

The Fair Maps SC campaign proposes a legally binding process that allows 15% of a county’s voters to petition their county council to adopt a resolution like the Joint Resolution for a Constitutional Amendment we introduced in 2018 (see page 10). The county petition shall be adopted or placed on the ballot of the next county-wide election, scheduled state-wide for November 2020.

The majority of the 170 members of the General Assembly are elected in party primaries and run unopposed in the general election. Less than 15% of voters participate in party primaries, yet an overwhelming majority of citizens believe that politicians shouldn’t draw their own districts. We predict that the county petitions for fair districts will garner more votes in legislators’ districts than were cast in the uncontested primary that elected them.

At the start of the 2020 legislative session, we will present lawmakers with the formal resolution from their county council showing the number of voters in their district who want them to put the amendment on the November 2020 ballot. Those who don’t support the amendment by the time filing opens on March 16 risk facing an opponent who does.

If two-thirds of the General Assembly doesn’t vote to place the Amendment on the ballot by the end of the session, the campaign will continue gathering signatures at the polls in November, where it will be clear to voters that there was only one legislative candidate on their ballot.

By law, ballot initiatives are nonpartisan. Online tools allow voters to download and print a petition, gather signatures, and mail it in to the campaign (see pages 12 and 13). Prepaid postcard petitions and social media can help the campaign succeed by the end of 2019. If we have not gathered enough petitions by then, the campaign will continue until South Carolina voters get to pick their politicians.

Making the case for a citizens redistricting commission

Problem 1

Gerrymandered maps let politicians pick their voters

Fact: South Carolina has one of the least competitive state legislative districts in the nation.

Under the current system, electoral maps are drawn by the state legislature, determined by majority vote, and subject to the governor’s veto. No state law establishes criteria for creating congressional and state legislative districts. Senate and House redistricting committees adopt their own guidelines, which are neither consistent nor precisely parallel. House guidelines expressly protect incumbents:

“Incumbency protection shall be considered in the reapportionment process. Reasonable efforts shall be made to ensure that incumbent legislators remain in their current districts. Reasonable efforts shall be made to ensure that incumbent legislators are not placed into districts where they will be compelled to run against other incumbent members of the South Carolina House of Representatives.”

Senate guidelines only suggest that districts should be of contiguous geography and, where practical and appropriate, give consideration to communities of interest, constituent consistency, county boundaries, municipal boundaries, voting precinct boundaries, and district compactness. The guidelines may be changed at any time.

Allowing legislators to draw their own districts is a conflict of interest that allows them to cherry-pick their voters. The current process leaves electoral maps vulnerable to partisan and racial bias, manipulated without public scrutiny. South Carolina politicians have taken advantage of this power to draw maps that virtually guarantee their re-election, and have adopted guidelines to protect themselves.

This unfair practice of creating boundaries of electoral districts to favor specific political interests is called gerrymandering, and gives one political party an unfair advantage on Election Day. It allows politicians to choose their voters instead of voters choosing their politicians. The biggest loser in this rigged system is South Carolina voters.

Bottom line: gerrymandering subverts equal representation, suppresses voter participation and diminishes good governance.

Problem 2

The courts say it’s up to politicians to fix our system, but they are unlikely to do so since it works for them

The electoral game in South Carolina is so rigged that more than 2.1 million of the state’s 3.1 million registered voters only have one candidate on their ballot for House or Senate. Of the 170 members of the state’s General Assembly, 69% had no opposition in the last two general elections. Only 10% of the seats (17) are competitive, where the victor wins with less than 60% of the vote.

The lack of competitive districts and the creation of safe seats means that we can’t vote our way out of the problem without changing the demographics of the districts. Since current maps were drawn by incumbents in 2012 to ensure their re-election, they are unlikely to reapportion their districts to include people who don’t look and think like they do.

The “partisan” gerrymandering that the courts have approved looks just like racial gerrymandering, as the current maps created 43 minority-majority districts by packing them with black voters. The Democratic Party is a now a majority-black party, and black legislators comprise a majority of the Democratic legislative caucus.

With its recent ruling on gerrymandering in Rucho v. Common Cause, the US Supreme Court in June 2019 affirmed Fair Maps SC’s prediction that the courts would hold that the US Constitution grants states, not the federal government, the power to run their elections.

With no recourse in federal court, and with the majority party unlikely to let voters draw district maps, it is left to us, the citizens of South Carolina, to construct a mechanism to force change. Here’s how we do that.

The Solution, Part 1

• Create an independent Citizens Redistricting Commission to draw fair maps

• Pass a Constitutional Amendment to allow citizens to vote for fair maps

In December 2018, the Citizens Redistricting Commission Act (H-3432 & S-254) and a Joint Resolution for a State Constitutional Amendment (H-3390 & S-249) were introduced. Taken together, they provide detailed legislation to turn redistricting over to the voters, and a Constitutional Amendment to prevent a legislative majority from overturning the decision. This would ensure that political power and public policy are more directly derived from the needs and aspirations of a majority of voters.

The Commission would be required to follow strict criteria in drawing district maps that could not give a disproportionate or unfair advantage to any political party or candidate. The commission would be charged with creating competitive districts where possible. Our current gerrymandered maps result in 117 district elections with only one candidate and 90% of the General Assembly winning by more than 60% of the vote.

The model maps in this toolkit use a demographic metric of winners taking office with no more than 60% of the vote. This would increase the number of competitive districts from 17 to 85 of the state’s 170 districts. This plan would increase competition by 500%, compelling candidates to appeal to all voters rather than a select few. Our maps show that making half the seats in the General Assembly competitive will still leave the Republican party in the majority. But Republican and Democratic legislators in newly competitive districts with general election competition could rise from 10% to 50%, creating a sensible center for sound public policies.

The Process

How a Citizens Redistricting Commission would work

The State Ethics Commission would work with the State Election Commission to identify eligible registered voters and invite them to apply for the commission. To be eligible, a voter must possess a consistent record of regularly voting in primary elections.

This does not apply to newly registered voters or those who have not had primary contests on their ballot. Politicians, lobbyists, and anyone with significant conflicts of interest cannot serve on the commission.

The Ethics Commission would then randomly select applicants (like a jury) from the general pool to create a 56-member nominee pool. That pool must include eight residents from each of the state’s seven congressional districts. Four of those nominees from each district must be majority-party voters, and four must be voters of the largest minority party.

The Ethics Commission would then review the nominee pool to ensure eligibility and to see that applicants mirror the state’s geographic and demographic makeup. Once completed, the Ethics Commission would randomly select from the pool 14 Redistricting Commission members and 14 alternates, one majority-party voter and one largest-minority party voter from each congressional district. Candidates would be selected to insure a demographic reflection of the district’s voters.

The Redistricting Commission would be provided the necessary resources and tools to assist in drawing maps. With today’s computer software, drawing fair maps is easy. It’s gerrymandering that is difficult. Strong rules would make the process fair, impartial, and transparent. To ensure transparency and accountability, minutes of all meetings shall be publicly posted on the Commission’s web site.

The Commission would be required to follow strict criteria when drawing the maps that would not give disproportionate advantage to any party or candidate. The Commission must consider five factors in this priority order: population equality, federal Voting Rights Act compliance, communities of interest, competitiveness of districts; and consistency with existing local boundaries.

The proposed maps must have districts that are of equal population as determined by the count of the 2020 US Census; are geographically contiguous; reflect the state’s diverse population and communities of interest; do not provide a disproportionate advantage to any political party; reflect consideration of county, city, and township boundaries; and are reasonably compact. The Commission shall, within all other constraints, also strive to make districts competitive.

The Commission must conduct its business publicly, and must publish everything used to draw the maps, including the data and computer software used. The Commission would be required to hold at least seven public hearings across the state to hear how communities want to be represented in districts.

The public would be able to submit feedback — even potential maps — for consideration. The Commission must post the maps on its web site for public comment in a manner designed to achieve the widest public access reasonably possible.

Prior to adoption, the maps must be tested using appropriate technology to ensure compliance with all mandated criteria. The final maps must be approved by at least 10 Commission members, including at least four majority-party members and four largest-minority party members. If the unable to reach agreement, the Ethics Commission would dissolve the original Commission and convene the alternate redistricting commission within 14 calendar days of the original commission’s dissolution. The alternate commission would have 60 days to conclude the reapportionment duties.

There is no executive or legislative power to alter or veto the Commission’s final reapportionment plan and maps.

The Solution, Part 2

How do we pull this off without the courts or the legislature?

The pressure to force this plan through a system resistant to change is found in the South Carolina Code of Law. While voters in South Carolina cannot put a constitutional amendment on the state ballot, they can petition county councils to adopt a resolution expressing the policy of the county’s citizens.

State law on county petition initiatives

Title 4 – Counties, Chapter 9: Article 13

Article 13, Initiative and Referendum

SECTION 4-9-1210. Electors may propose and adopt or reject certain ordinances; submission by petition to council.

The qualified electors of any county may propose any ordinance, except an ordinance appropriating money or authorizing the levy of taxes, and adopt or reject such ordinance at the polls. Any initiated ordinance may be submitted to the council by a petition signed by qualified electors of the county equal in number to at least fifteen percent of the qualified electors of the county.

SECTION 4-9-1230. Election shall be held where council fails to adopt or repeal ordinance. If the council shall fail to pass an ordinance proposed by initiative petition or shall pass it in a form substantially different from that set forth in the petition therefor or if the council shall fail to repeal an ordinance for which a petition for repeal has been presented, the adoption or repeal of the ordinance concerned shall be submitted to the electors not less than thirty days nor more than one year from the date the council takes its final vote thereon.

The council may, in its discretion, and if no regular election is to be held within such period, provide for a special election.

All county councils shall be bound by the results of any such referendum.

County Petition Guidelines

Using the law to end gerrymandering

State laws that empower county and municipal voters to make ordinances and resolutions have not been used by citizens to change local or state policies. The county referendum process is regularly used by local governments, without taking up petitions, to levy taxes for a library, school district, or public transportation.

This law prohibits citizens from using the petition process to spend or raise tax money, as only elected officials can do that. It does, however, empower county voters to petition to pass a resolution, or ordinance, that sets the county’s official policy position.

County policies cannot over-ride state laws, but a successful county petition isn’t an opinion poll; it is a legally constituted resolution passed by county councils advising their legislative delegations that the citizens of their county and district have resolved, in this case, that the Amendment to end gerrymandering should be on the November ballot.

Our plan to compel legislators to put the Citizens Redistricting Commission Amendment on the general election ballot is to get more of their constituents to sign the county petition than voted for the incumbent legislator’s uncontested primary. Legislators who ignore the expressed will of their voters do so at their own peril.

Petition targets, distribution, collection, and verification

This is not the usual petition drive that is an organization’s promotional ploy that will end up in the trash. The petitions for the Fair Maps SC campaign are legal documents. As with all voting related documents, there are strict rules to follow and criminal penalties for their wilful violation.

Laws regulating the county petition campaign provide that:

1. Only registered voters of a county can sign that county’s petition.

2. Specific language that Fair Maps is using in both the county petition and the State Constitutional Amendment.

3. The size and nature of the petitions is not specified, but should be standardized to facilitate verification. (The petition is included on page 13, and is posted at FairMapsSC.com, where it can be downloaded, filled out, and the original mailed to: Fair Maps SC, PO Box 8325, Columbia, SC 29202. Online distribution of the blank form allows any SC voter to gather signatures. With funding, petitions can be printed in newspapers and on prepaid post cards.)

4. A valid petition must contain the voter’s printed name, signature, date of birth, and indicate their county of registration. Only original petitions with original signatures are valid.

5. Original petitions must be submitted at one time to county election boards. Petitions will be verified prior to submission by trained volunteers to ensure a correct count of registered votes allocated to each county and legislative district. County election boards are required to validate the petitions to ensure that they include at least 15% of the county’s registered voters. Numbers for each district are posted at FairMapsSC.com.

Verifying a voter’s registration

The State Election Commission’s web site (scvotes.org) and mobile application now allow anyone to enter the name, date of birth, and county of registration to verify the political districts in which voters are registered. Any citizen that is unregistered but eligible to vote can be registered immediately prior to signing the petition by using the State Election Commission’s online tools.

Which organizations can engage in a ballot initiative campaign?

Referendums are by law nonpartisan, as they reflect the will of the people rather than a party or candidate. So educational work around petitioning to end gerrymandering can be done in churches, schools, and civic institutions that are restrained from political engagement.

501(c)(3) public charities may legally express positions on ballot initiatives, referenda, state constitutional amendments, county resolutions, and other policies put to a direct vote of the public. (They must not suggest support or opposition to any candidates for public office).

Ballot measure advocacy can be an important tool for public charities to help create better laws for the communities they serve. They are often used to tackle issues not adequately resolved by current state policy or those that elected representatives don’t want to sponsor.

Working on ballot measures may help organizations connect with individuals or communities they might not otherwise. Advocacy for the adoption or rejection of ballot measures usually qualifies as lobbying under federal tax law, which is permitted, within limits, for 501(c)(3) public charities.

Federally chartered 501-c-3 organizations (ie. advocacy, civic, educational, and religious) may share strategies and information with all parties supporting a ballot measure as long as they never show support or opposition to particular candidates for public office. C-3’s can do surveys and reports on the positions of incumbents and candidates, and take contributions for their nonpartisan educational work from all sources, within federal constraints on lobbying expenses as part of their budgets. There are no prohibitions on political parties and clubs participating in a ballot initiative.

South Carolina’s ethics laws consider that ballot measures only come from the legislature, and the Ethics Commission reporting rules govern opposition or support of a question on the state ballot. It is unclear what financial rules, if any, govern independent expenditures to promote a county level referendum.

Should the Fair Maps SC amendment make it to the state ballot, the Fair Maps campaign would have to register as a ballot measure campaign, make quarterly reports to the State Ethics Commission, and observe contribution limits of $3,500.

Organizations and individuals involved in ballot measure campaigns in South Carolina must adhere to the state’s campaign finance laws. These laws regulate the amounts and sources of money given or received for political purposes. In addition, campaign finance laws stipulate disclosure requirements for political contributions and expenditures towards a ballot measure.

For detailed information regarding 501-c-3 and c-4 lobbying, see Alliance for Justice. For state regulations, go to ethics.sc.gov.

Targeting the petition to gain legislative support

To be clear, even a successful 46-county petition drive cannot automatically place the constitutional amendment to end gerrymandering on the statewide ballot. Only a two-thirds vote in the General Assembly can do so.

Republicans hold majorities in all three branches of our state government. They have the majority in the House and Senate necessary to pass new district maps without a single Democratic vote. Since demographics dictate that Democrats will remain a minority party, Republicans let them make their districts safe for their incumbents.

In fact, packing black voters into certain districts means a Democrat will likely win there, but it also helps ensure the creation of more safe, majority-white districts for Republicans. So incumbents of both parties benefit from having gerrymandered districts.

Well over a half-million black and white voters — packed in and cracked out of these safe districts — won’t benefit, as their legislator doesn’t need their vote to win their primary. In fact, 40% of black voters only have a white Republican on their ballot for Senate, and one out of every eight white voters (274,404) only have a black candidate on their ballot.

When the choice of who represents YOU is repeatedly made by a small percentage of people who don’t resemble you, your elected representative doesn’t have to represent you to win. To get our amendment on the ballot, we must convince all 44 Democrats and at least 39 Republicans in the House, along with 12 Republican Senators and all 19 Democratic Senators to get the necessary 114 votes to put the amendment on the ballot.

We have no doubt that if we can get the amendment on the ballot it will pass.

Once approved by the voters, the amendment then returns to the legislature for ratification by a simple majority. Even then, we will face challenges in making sure that enabling legislation and funding for a Citizens Redistricting Commission is true to the intent of our effort.

Gaining the bipartisan leadership and popular support to end gerrymandering will require a shared belief that we’re all better off when we’re all better off. Fair maps can make half the seats in the legislature competitive enough that the winning candidate will have to represent people who don’t look like them or think like them. This can create a sensible center in South Carolina state government that will be more responsive to, and responsible for, all constituents.

The county petition campaign will focus on legislative districts where the incumbent has not agreed to let their constituents vote on the amendment. We have the tools to tally petitions by district and direct resources to pressure reluctant incumbents.

The targeting we plan to do starts with a publicly posted and regularly updated list of how the incumbents stand on the constitutional amendment. This requires an educational and grassroots lobbying effort with each legislator to inform them of the opportunity to end gerrymandering and solicit their position. We will target legislators who control the committees the legislation will have to pass through to get to the floor and on the ballot.

On the first day of the 2020 legislative session, we will release the list of legislators who have agreed to vote to put the Amendment on general election ballot, and adjust our tactics accordingly.